PAC Partner, Suzanne Hanchett, is publishing this obituary for a colleague and friend in the newsletter of the Society for Applied Anthropology:

Gisele Maynard-Tucker, a medical and applied anthropologist, died of a lung disease on August 23, 2021, at the age of 84. She was a Fellow of the Society for Applied Anthropology and a member of the American Anthropological Association and the American Public Health Association. She had been a Research Scholar at the UCLA Center for the Study of Women since 1989. Trained as a classical pianist, Gisele grew up in Nice, France. She moved to California in the late 1950s or early 1960s.

Ethnographic research in a Quechua community during three summers in highland Peru (1981, 1984, and 1986) was the basis of her master’s thesis at California State University Northridge, and also her 1988 UCLA doctoral dissertation, “Reproductive Decision-making and the Use of Modern Contraceptives in Rural Peru.”

Gisele had a long and productive career. After completing her Ph.D. she served as a Research and Evaluation Advisor for the International Planned Parenthood Foundation in Haiti from mid-1989 to mid-1991– a time of political turmoil and street violence. She developed a way to test the effectiveness of rural clinics by deploying “mystery clients,” local women who came in for services and reported on how they were treated.

Fluent in French, English, Spanish, Quechua, and Haitian Creole, she worked for more than 20 years as an independent consultant after 1991, doing research and evaluation on reproductive health issues – e.g., family planning, abortion, maternal mortality, child survival, and HIV/AIDS prevention — for the World Health Organization, the United Nations Population Fund, USAID, the World Bank, the European Union, POPTECH, Development Associates, Academy for Educational Development, and other agencies in at least 15 different countries: Benin, Cameroon, Senegal, Malawi, Nigeria, Madagascar, Morocco, Guinea, Peru, Bolivia, Guatemala, Haiti, Indonesia, India, and Nepal. She published numerous articles and one book, Rural Women’s Sexuality, Reproductive Health and Illiteracy: A Critical Perspective on Development (Lexington Books, 2015)

Her work sets a good example for the ways that anthropological training can inform and help to modify health and social development programs. Her evaluation studies and her publications draw attention to the ways that development programs may fail to reach so-called “beneficiaries,” people at the end of convoluted chains of funding and decision-making, chains that extend down from donors to administrative agencies, through national and local government offices, and perhaps on to local communities. Poor coordination among donors can overwhelm government agencies trying to meet multiple reporting demands. (This problem lessened somewhat after 2005.) She drew attention to the potential for corruption at all levels of these systems, and especially to inequalities between urban areas and more remote rural villages with poor transportation infrastructure, low literacy rates, and much out-migration of men.

Her writings featured numerous case studies illustrating women’s social and economic problems, revealing her strong capacity for empathy. She was a godmother to the children of some close Quechua friends-cum-informants in Peru; the women accepted her as a comadre. She often mentioned the importance of trust, friendship, and respect as the best guarantees of reliability in qualitative analysis. She argued consistently that planners must listen to voices from rural areas and utilize “participatory” development approaches (such as focus group discussions and participant observation) in combination with questionnaire surveys. Top-down planning approaches could not succeed, in her view.

The practical challenges facing rural women, and the manipulation of women’s sexuality, however, were her strongest focus. Her work brought her into contact with many different situations facing sex workers, wives, single women, and their male partners. She probed into the ways that decisions were made — to use condoms and contraceptives or not, to have children in order to keep a man, to sell sex to survive – decisions made by women whose sexuality is their most productive asset. She noted that rural women often combine folk treatments and modern medicine, and that daily routines, lack of education, and competing cultural frameworks can lead to mistakes in using modern medicines, especially when clinical services are weakly funded and insensitively delivered. She documented the damage that the Hyde Amendment did to USAID’s international family planning programs in her most recent writings.

She decried universally patriarchal attitudes devaluing women, and also the fact that women cannot own land in societies with patrilineal inheritance. She observed that HIV/AIDS prevention programs offering clinical services to professional sex workers will not help married women who sell sex when they run out of money. She explained that abortion (safe or otherwise) is a common response to unwanted pregnancy eveerywhere. She analyzed and supported effective programs intended to help disadvantaged women or to promote girls’ education and empowerment. And she sharply criticized ineffective ones. Her reflections on an unsuccessful Madagascar sex workers’ project show how deeply she engaged with the people she encountered:

This experience has been full of hope and frustration, for the members of the AFSA and the anthropologist. At last, the project might have brought a new dimension in the life of the sex workers even so it was not successful in promoting a sustainable change of attitudes and economic support. This essay illustrates the ethical debate concerning the role of the anthropolo gist as scholar, change agent, and human being involved in complex situations in which resolutions influence the lives of informants. Would I get involved again? Yes, but with less haste and more preparation for the feasibility and sustainability of the project.(2002)

As a Nigerian colleague, Olusina Olusegun said of Gisele, “She pays attention and [wants] to see the young people grow.” Gisele and I conducted workshops at SfAA meetings from 2013 to 2016 for students interested in building careers in international development. Students greatly appreciated her insights and strong communication skills. Her warm personality and dedication to women’s welfare brought a fully human perspective to all her social research and evaluation work.

Gisele Maynard was born in 1936. Her husband, Edward (Tony) Tucker, died in 1992. She is survived by her son, Nicolas Tucker. Her loss is also deeply mourned by Daniel Simmons, her close companion of 20 years.

The accomplishments and effectiveness of Gisele Maynard-Tucker make it abundantly clear that applied anthropology can contribute to making the world a better place for those too often left behind.

Suzanne Hanchett

Planning Alternatives for Change LLC

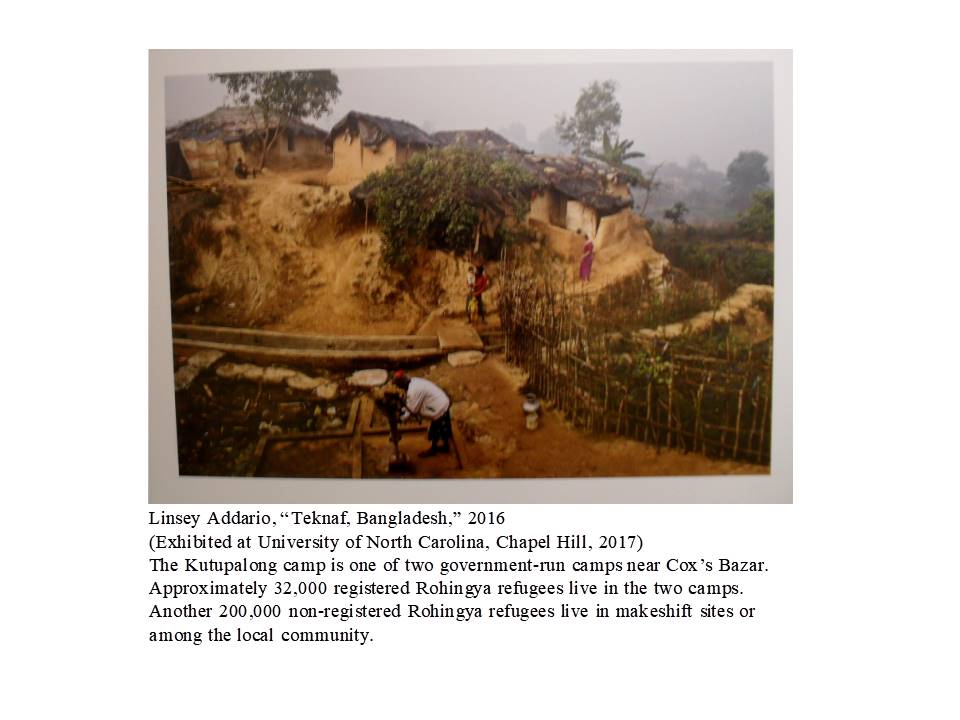

PAC Associate Anwar Islam in 2019 visited Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, on an assignment. He offers a case study of a Rohingya man living in a refugee camp.

A ROHINGYA MAN LANGUISHING IN A BANGLADESH REFUGEE CAMP

Case Study by Anwar Islam, PAC Associate

Location: Camp-15, Jamtoli, Cox’s Bazaar

29 June 2019

Md Younus Ali, a healthy 80-year-old man (probin ‘elder’ in Bengali), now lives in a Rohingya Camp at Ukheya in Cox’s Bazaar District in Bangladesh. He was born in Myanmar. Younus’s father and mother were 72 & 65 years of age when they died. He never met his maternal grandparents, but they both died at advanced ages. Younus was educated up to the sixth standard in the Burmese language in a Rohingya school at his original birth place. He, his wife, four daughters & a abandoned nephew were evicted from Myanmar in 2017. The displaced family has gotten temporary shelter and help from many sources. The Bangladesh Government, international agencies, NGOs, and private companies are taking care of the camps. Settlers are provided with two-room houses that have bamboo roofs and walls. Five families share one ring-slab latrine, and there is a single hand-pumped tube well for the use of 40, 50, or more families. “Water scarcity is the other name of hell,” he says. In the peak of summer, the water table goes down. With no trees, no shade, and no wind, all family members become sick. Now time passes slowly, and life is boring for them all. Younus has no peace of mind.

The World Food Programme provides some food for the family: rice, pulses, and cooking oil. But the amounts of food aren’t sufficient for the family. They eat only twice each day, one full meal and one half meal, and they go without food instead of taking a third meal. The minimal facilities & uncertain existence cause big tensions in this family. In addition, the inadequate water & poor sanitation facilities are producing diseases, mental tension.

Younus & his wife recently faced a new problem. A few days ago their 17-year-old daughter fell down into a latrine pit, which collapsed because of its poor design and low cost, poor quality latrine rings. Their daughter’s hand was fractured in this incident. Younus’s wife is becoming thin from worrying about their daughter’s future. They have no son. This uncomfortable situation makes Younus feel that he is in a jail. Sometimes he thinks of suicide as a way of escaping the unbearable facts of his life here. But the family has no alternative. They must stay in the camps. Younus often thinks they are wasting their lives in this place. He fears that this situation will decrease the whole family’s life expectancy. Younus wants to live to a ripe old age, as his father’s generation did.

© Planning Alternatives for Change, LLC, 2019. Available for any non-commercial use. Key words: Rohingya, Refugees, Displaced persons, Bangladesh, Myanmar